By Colin Gordon & Jay Bowen

Featured Item or Collection: Dividing the City

What is the item?

These items feature data on covenant restrictions in St. Louis. They are part of an effort to document the spatial distribution and extent of a mechanism widely understood to be a root cause of ongoing racial segregation and wealth inequality. They make visible these efforts to maintain racially divided access to property and wealth, which were long concealed in the extended pages of local records.

What BTAA Library submitted the item?

University of Iowa

Interesting tidbits

- An outgrowth of the Mapping Prejudice project initiated at the University of Minnesota

- The uneven digitization of property records including racial restrictions presented unique impediments to reproducing the research in Greater St. Louis, Missouri

- The expansion of private racial restrictions in the St. Louis region were mapped from the late nineteenth century to their decline with Shelley v Kraemer in 1948

- Mapping this quantity of data in interactive format also presented issues with responsiveness that were solved by converting the geojson polygon data to vector tiles

- Such restrictions calcified notions about racial homogeneity and property value in US cities that have continued to impact educational opportunity, economic mobility, and intergenerational wealth

Inspired by the work of researchers and community activists in Minneapolis (Mapping Prejudice) and Seattle (Segregated Seattle), we set out to document the use of racial restrictions on property in St. Louis in the first half of the 20th century. Such restrictions are widely understood to constitute the root cause of racial segregation and lasting disparities in racial wealth, and the foundation of local and federal policies that succeeded them. And yet, because the restrictions themselves are buried in local property records, they have proven difficult to document.

St. Louis Deed Book 1121-525 (1893), p3.

In some settings (including Minneapolis) the digitization of records has enabled "distant reading" through optical character recognition. In St. Louis City and St. Louis County, however, the records are unevenly digitized and—for the era of private restriction—largely handwritten. So we needed a different research strategy. We were able to exploit a wrinkle in local recording conventions: In Missouri, as in a few other settings, county recorders not only documented restrictions in individual deeds, but also required developers and realtors to file "master agreements" covering entire subdivisions or neighborhoods. In both St. Louis and St. Louis County, such agreements are filed with a regular run of deed records or plat maps. Additionally, they are indexed separately from the "grantor and grantee" index that otherwise governs the organization of deed books. In St. Louis City, this was by one of the local title companies; in St. Louis County this was by the recorder themselves.

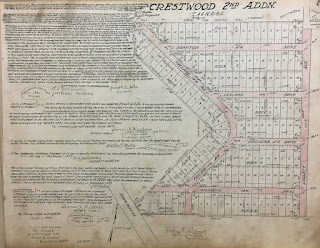

Crestwood (1928), Plat Book 26-25

In each jurisdiction, we collected the effective date, language, terms, and scope of each restrictive indenture or agreement. Using the current county assessor or recorder shapefile of property parcels, we used stable legal descriptions (common to historical and current records) to match historical restrictions to current parcels. This enabled us to map the trajectory and reach of private racial restrictions, from their earliest iterations in the late nineteenth century, through the explosion of their use in response to the First and Second Great Migrations (especially during the housing boom of the 1920s), to the abrupt decline in the practice after the Supreme Court decision in Shelley v Kraemer (1948).

Racial Restrictions in Greater St. Louis, 1870 - 1952

Starting from these linked data in shapefile format, we endeavored to build an interactive map of the nearly 100,000 restricted parcels in St. Louis and St. Louis County. Mapping such a large quantity of data proved initially to be a challenge. Early efforts at producing an interactive map using Leaflet JS to pull from large files in GeoJSON format resulted in slow loading and sluggish map responsivity to the interactive elements, like the time slider, hover-activated tooltip, layer control, and zoom button. To avoid having to separate the map into city and county partitions, we opted to convert the GeoJSON data into vector tiles and handle the resulting tile set with another open-source map-oriented JavaScript library, MapLibre GL JS. With vector tiles, the map can shed unseen data and simplify polygons at smaller map scales. This allowed us to plot the full collection of restricted private parcel data without crashing the application, thereby providing the public with an uncomplicated visual account of racial segregation in Greater St. Louis that would otherwise remain concealed in overwhelming volumes of handwritten deeds and subdivision agreements.

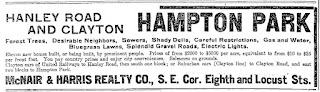

Real Estate Advertisement Promoting "Careful Restrictions" and "Desirable Neighbors"

These private restrictions were an important source of segregation and housing occupancy in their own right, setting the terms of racial occupancy in northern and border cities across a half century of dramatic urbanization and migration. It also served as the foundation for durable inequalities. In part, this was because its base assumptions—about property values, land use, and neighborhood homogeneity—were emulated and entrenched by local zoning and federal housing policies. In part, this was because, in the American context especially, so much else—including educational opportunity, economic mobility, and intergenerational wealth—flowed from those housing investments.

Our St. Louis research is hosted as the digital project "Dividing the City" by the University of Iowa Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio, and the mapping resources are mirrored by our community partner, the Equal Housing and Opportunity Council of Metropolitan St. Louis. For a digest of ongoing projects around the country, see the National Covenants Research Coalition.

Where can I find out more?

- To see the full project as well as further explanation of Dividing the City: Race-Restrictive Covenents in St. Louis and St. Louis County, you can view the website here

- To see the code behind the map, please go to this GitHub repository

- To see an explanation of how to generate custom vector tiles and map them with Maplibre GL JS, please read the instructions here

- To see recent press about this project, you may view the list of links here

Colin Gordon, Department of History, University of Iowa

Jay Bowen, University of Iowa Libraries, University of Iowa